Femoro-Acetabular Impingement (FAI): Causes, Types, and Treatment

Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) is a condition where abnormal contact between the femoral head (thigh bone) and the acetabulum (hip socket) causes damage to the hip joint.

Vasant BHANDI

11/1/20228 min read

Femoro-Acetabular Impingement (FAI)

Femoroacetabular impingement, commonly referred to as FAI, is a condition characterized by abnormal contact between the femoral head and the acetabulum of the hip joint. This interaction leads to a variety of symptoms including pain, limited range of motion, and can progressively result in osteoarthritis if left untreated. As its name suggests, FAI is an impingement issue that primarily occurs due to structural abnormalities of the hip joint, which can manifest in diverse forms.

Types of Femoro-Acetabular Impingement

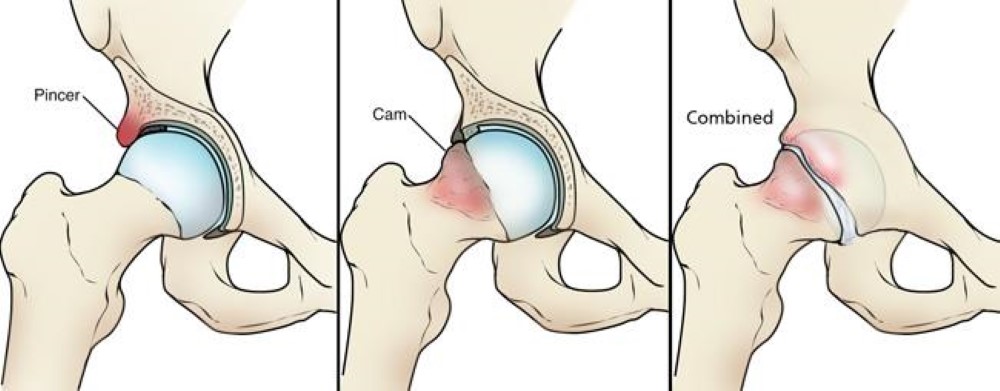

There are three primary types of femoroacetabular impingement: cam impingement, pincer impingement, and mixed impingement, each displaying distinct characteristics that can affect individuals differently. Understanding these types is crucial for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

1. Cam Impingement: In cam impingement, the femoral head is not perfectly spherical, which leads to abnormal contact with the acetabulum during leg movements. This irregularity can cause the femoral head to 'catch' on the edge of the acetabulum, resulting in pain and decreased mobility. Individuals with this type often experience discomfort during activities that require flexion of the hip, such as squatting or running.

2. Pincer Impingement: Conversely, pincer impingement occurs when the acetabulum covers an excessive portion of the femoral head. The extra coverage causes the rim of the hip socket to pinch the femur during movement, leading to symptoms similar to cam impingement. People with pincer impingement may also feel pain in the groin area and restrictions in their hip motion during everyday activities.

3. Mixed Impingement: Mixed impingement is a combination of both cam and pincer types. Patients presenting with this variation might experience a complex range of symptoms, given the dual mechanisms of impingement at play. Treatment often requires a tailored approach to address both structural issues and alleviate symptoms.

Symptoms

Groin pain, especially during or after activity

Stiffness or reduced range of motion in the hip

Pain with prolonged sitting, standing, or twisting movements

Clicking, locking, or catching sensations in the hip

Causes and Risk Factors

Congenital or developmental hip abnormalities

High-impact activities or sports that stress the hip joint

Repeated hip injuries

Genetics may also play a role in predisposing individuals to FAI.

Diagnosis

Clinical Exam: A healthcare provider assesses pain, range of motion, and specific impingement tests like the FADIR (Flexion, Adduction, Internal Rotation) test.

Imaging: X-rays, MRI, or CT scans can identify structural abnormalities and assess joint damage.

Treatment

Non-Surgical

Physical therapy to improve hip mobility, strength, and stability

Activity modification to reduce strain on the hip

Anti-inflammatory medications or injections to manage pain

Surgical

If symptoms persist despite conservative treatment, arthroscopic surgery may be performed to reshape the hip joint and repair any damage.

Prevention and Management

Engage in activities that promote joint health, such as low-impact exercises like swimming or cycling.

Avoid repetitive movements that stress the hip joint.

Early intervention for hip pain can prevent progression of joint damage.

Clinical Signs and Tests

1. History and Symptoms

Pincer Impingement:

Symptoms often develop gradually.

Pain may be felt deep in the groin, especially during prolonged sitting, standing, or hip flexion activities.

May be more common in middle-aged women.

Cam Impingement:

Symptoms may occur after activities involving repeated hip flexion (e.g., sports like soccer or hockey).

Groin pain that worsens with activities like squatting or pivoting.

May present in younger, more athletic individuals, often males.

2. Physical Examination

Both types of FAI share overlapping tests, but subtle patterns can indicate the type of impingement.

General Signs:

Limited hip flexion, internal rotation, or abduction.

Groin pain reproduced during physical tests.

Specific Tests:

FADIR Test (Flexion, Adduction, Internal Rotation):

The examiner flexes the hip to 90°, then adds adduction and internal rotation.

Positive for both cam and pincer FAI if groin pain is reproduced.

FABER Test (Flexion, Abduction, External Rotation):

Used to detect acetabular or labral pathology. Pain in the groin may indicate pincer impingement.

Distinguishing Features:

Cam Impingement:

Limited hip internal rotation in flexion.

Pain during deep squatting or pivoting movements.

Pincer Impingement:

Pain is often less positional and more persistent.

Associated with over-coverage; symptoms may include labral damage leading to secondary stiffness.

Imaging Studies (Essential for Confirmation)

X-rays:

Cam Impingement:

Look for an aspherical femoral head or a "bump" at the femoral head-neck junction.

An alpha angle >55° on imaging suggests cam impingement.

Pincer Impingement:

Assess for acetabular over-coverage (e.g., a deep socket or crossover sign).

A center-edge angle >40° is a hallmark of pincer impingement.

MRI:

Identifies cartilage or labral damage, which can help differentiate between the two.

CT Scans:

Provides detailed 3D imaging for evaluating bone morphology in complex cases.

Key Differentiating Features

Feature

Cam Impingement

Pincer Impingement

Anatomy

Abnormal femoral head-neck junction

Over-coverage of femoral head by acetabulum

Pain Trigger

Deep squatting, twisting, pivoting

Prolonged sitting or standing

Age/Gender

Younger males, athletes

Middle-aged females

X-ray Findings

Increased alpha angle (>55°)

Deep socket, crossover sign

Interpreting Imaging Results for Cam and Pincer Impingement

Imaging studies are critical for confirming the diagnosis and distinguishing between cam and pincer impingement. Here's a breakdown of key findings for each modality:

1. X-Rays (Initial Diagnostic Imaging)

Cam Impingement Findings:

Alpha Angle:

Measures the shape of the femoral head and neck junction.

Definition: The angle formed between a line connecting the center of the femoral head and the neck axis, and a second line extending to where the femoral head loses its round contour.

Abnormal: An alpha angle >55° suggests cam deformity.

Best seen on a frog-leg lateral view or Dunn view.

Bump or Flattening:

Visible at the femoral head-neck junction.

Seen on lateral views of the hip (e.g., frog-leg lateral or cross-table lateral).

Pincer Impingement Findings:

Crossover Sign:

Indicates acetabular retroversion.

Definition: The anterior wall of the acetabulum crosses over the posterior wall on anteroposterior (AP) X-ray.

Center-Edge Angle (CEA):

Measures the amount of acetabular coverage over the femoral head.

Abnormal: A CEA >40° suggests acetabular over-coverage.

Measured on an AP pelvis view.

Ischial Spine Sign:

Prominent ischial spine visible on an AP view, indicating acetabular retroversion.

Protrusio Acetabuli:

The femoral head projects medially beyond the ilioischial line (Köhler’s line), indicating severe over-coverage.

2. MRI (Soft Tissue and Cartilage Assessment)

MRI is used to detect:

Labral Tears:

Common in both cam and pincer impingement.

Look for detachment of the labrum from the acetabulum in pincer FAI.

Cartilage Damage:

Cam impingement: Chondral delamination or damage at the acetabulum, particularly anterosuperiorly.

Pincer impingement: Chondral damage from over-coverage, often along the acetabular rim.

Bone Edema:

May indicate stress or early degeneration.

MRI arthrograms (contrast-enhanced MRI) provide better visualization of the labrum and cartilage.

3. CT Scans (Detailed Bone Morphology)

CT scans with 3D reconstruction offer detailed evaluation of:

Femoral Head-Neck Junction:

Assess cam deformity more precisely, especially if X-ray findings are unclear.

Acetabular Coverage:

Useful in borderline cases to confirm pincer impingement.

Version Abnormalities:

Retroversion of the acetabulum in pincer impingement.

Excessive femoral anteversion or retroversion.

Clinical Example

Case 1: Suspected Cam Impingement

Young male athlete with groin pain during squatting.

FADIR test: Positive for groin pain.

X-ray: Increased alpha angle (e.g., 65°), aspherical femoral head-neck junction on Dunn view.

MRI: Anterosuperior cartilage damage and labral delamination.

Case 2: Suspected Pincer Impingement

Middle-aged woman with persistent groin pain during prolonged sitting.

FABER test: Reproduces pain in the groin.

X-ray: Crossover sign and center-edge angle of 45° on AP pelvis view.

MRI: Labral detachment and acetabular rim edema.

Phase-Wise Rehabilitation for Non-Operative Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI)

Non-operative management for FAI focuses on reducing pain, improving hip function, and preventing further damage. Rehabilitation is divided into phases, with specific goals and precautions at each stage.

Phase 1: Acute Phase (Pain Relief & Inflammation Reduction)

Duration: 2–4 weeks (depends on severity).

Goals:

Reduce pain and inflammation.

Protect the joint from further irritation.

Improve mobility without aggravating symptoms.

Do's:

Rest: Avoid activities that worsen symptoms (e.g., deep squatting, twisting).

Modify Activity: Use a more neutral range of hip motion. Avoid repetitive flexion beyond 90°.

Gentle Mobility Exercises:

Supine hip flexion (partial range).

Hip pendulum movements.

Cat-cow for lumbar and pelvis mobility.

Isometric Strengthening:

Glute bridges.

Quadriceps and hamstring sets.

Pain Management:

Use ice or heat as appropriate.

Consider NSAIDs if recommended by a physician.

Don’ts:

Do not push through sharp or pinching pain during exercises.

Avoid high-impact activities like running or jumping.

Avoid deep hip flexion (e.g., sitting cross-legged or deep lunges).

Phase 2: Intermediate Phase (Strengthening & Mobility)

Duration: 4–8 weeks.

Goals:

Improve strength and control of surrounding musculature (glutes, core).

Restore pain-free range of motion (ROM).

Transition from isometric to isotonic exercises.

Do's:

Strengthening Exercises:

Gluteal Focus:

Clamshells (use a resistance band).

Side-lying hip abduction.

Core Stability:

Dead bugs.

Bird-dogs.

Functional Movements:

Step-ups with controlled eccentric lowering.

Mini squats (avoid going beyond 45°).

Dynamic Stretching:

Hip flexor stretches (gentle).

Piriformis stretches.

Low-Impact Aerobic Activity:

Stationary cycling or swimming.

Don’ts:

Avoid excessive loading (e.g., heavy weights) until proper form is established.

Do not perform exercises that cause groin pain or pinching.

Avoid hip hyperextension and extreme internal/external rotation.

Phase 3: Advanced Strengthening & Functional Movement

Duration: 8–12 weeks.

Goals:

Build strength in all planes of hip movement.

Enhance functional mobility and stability for daily activities.

Prepare for return to sport (if applicable).

Do's:

Strengthening:

Single-leg exercises:

Bulgarian split squats (shallow depth).

Single-leg Romanian deadlifts.

Side planks to strengthen the gluteus medius.

Resistance band walks (sideways or forward/backward).

Dynamic Functional Movements:

Controlled lunges (ensure pain-free ROM).

Lateral step-ups and step-downs.

Proprioceptive Training:

Balance exercises (e.g., single-leg stance on an unstable surface).

Low-Impact Conditioning:

Elliptical, swimming, or light jogging if tolerated.

Don’ts:

Do not push into extreme ranges of motion (especially deep flexion or hyperextension).

Avoid ballistic movements (e.g., plyometrics) unless cleared.

Do not overload the joint too quickly. Progress gradually.

Phase 4: Return to Sport/Activity Phase

Duration: 12+ weeks (varies based on goals).

Goals:

Achieve full strength, stability, and control.

Safely return to sport or high-impact activities.

Do's:

Sport-Specific Training:

Gradual reintroduction of running or sport drills.

Plyometric exercises (e.g., box jumps, agility ladder) if appropriate.

Functional Strengthening:

Add resistance to previous exercises.

Dynamic movements like lateral lunges or rotational exercises.

Flexibility Maintenance:

Continue dynamic stretching routines.

Don’ts:

Avoid abrupt changes in intensity or volume of activity.

Do not skip strengthening exercises, as muscle imbalance may increase recurrence risk.

General Tips Throughout Rehabilitation

Monitor Pain: Mild discomfort is acceptable, but sharp or pinching pain means the activity is too aggressive.

Consistency: Gradual progress is key to success. Avoid rushing through phases.

Biomechanics: Maintain proper form to avoid compensatory patterns that stress the joint.

Collaboration: Work with a physical therapist for tailored progression and monitoring.

Considerations for Joint Injections in Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI)

Joint injections, typically involving corticosteroids or platelet-rich plasma (PRP), are sometimes used to manage pain and inflammation in FAI. These injections can provide temporary relief, aid in diagnosis, or facilitate participation in physical therapy. Here are key considerations:

1. Purpose of the Injection

Diagnostic:

To confirm the hip joint as the primary pain source (using a local anesthetic).

If pain relief occurs after injection, it suggests intra-articular pathology.

Therapeutic:

To reduce pain and inflammation, enabling more effective rehabilitation.

Often used when other conservative treatments fail.

2. Types of Injections

Corticosteroid Injections:

Reduce inflammation and provide short-term pain relief (weeks to months).

Commonly used in acute flare-ups or for patients with significant inflammation.

Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP):

A biologic treatment that may promote tissue healing and reduce symptoms.

Emerging as an alternative for patients who want to avoid steroids.

Hyaluronic Acid (Viscosupplementation):

Rarely used for FAI but may improve lubrication in cases of coexisting osteoarthritis.

3. Candidate Selection

Good Candidates:

Persistent pain unresponsive to standard conservative care (e.g., physical therapy, NSAIDs).

Diagnostic uncertainty regarding the source of pain (intra-articular vs. extra-articular).

Patients needing temporary symptom relief to engage in rehabilitation.

Not Ideal Candidates:

Significant structural damage (e.g., advanced osteoarthritis or labral tears requiring surgery).

History of severe adverse reactions to injections.

Active infections or compromised immune systems (increased infection risk).

4. Procedure Considerations

Imaging Guidance:

Use fluoroscopy or ultrasound to ensure accurate placement within the hip joint.

This minimizes risks and maximizes efficacy.

Preparation:

Avoid NSAIDs for a few days before PRP injections (if applicable) to ensure better platelet function.

Ensure sterile technique to reduce infection risk.

Aftercare:

Rest the joint for 24–48 hours post-injection.

Gradual return to activity as tolerated.

5. Potential Risks and Complications

Common (Transient):

Pain or discomfort at the injection site.

Temporary increase in symptoms ("steroid flare").

Less Common:

Infection (septic arthritis).

Bleeding or hematoma.

Allergic reaction to the anesthetic or steroid.

Fat atrophy or skin discoloration near the injection site (steroids).

6. Expected Outcomes

Corticosteroids:

Provide relief for 1–3 months, with effects varying among individuals.

Best suited for inflammatory conditions (e.g., synovitis).

PRP:

May take several weeks to show improvement.

Longer-lasting effects (up to 6–12 months) and may improve joint health.

7. Role in Non-Operative FAI Management

Injections are not a cure but a tool to complement other treatments.

Temporary relief can enable participation in physical therapy to strengthen muscles and improve joint mechanics.

Should not replace long-term interventions like activity modification or rehabilitation.

8. Frequency of Injections

Limit corticosteroid injections to 3–4 per year to avoid cartilage or soft tissue damage.

PRP can often be repeated as needed, depending on response and provider recommendations.

9. Alternatives to Injections

NSAIDs, heat/ice therapy, and physiotherapy as first-line treatments.

Consider lifestyle adjustments like weight management or activity modification.

Discussion with the Patient

Discuss potential benefits, limitations, and risks.

Set realistic expectations (injections may reduce symptoms but not address the underlying FAI morphology).

Assess patient preferences, especially regarding biologic vs. steroid-based treatments.

Get in Touch

Contacts

+44 75227 75979

contact@physiogenics.co.uk

vasant.bhandi@physiogenics.co.uk

Address

Tribes, 96A Clifton Hill London, NW8 0JT

Opening Hours

Monday-Sunday 9 AM to 7 PM (last appointment at 6PM)

We are here when you need us. 7 Days a week

PhysioGenics St John's Wood

PhysioGenics Harrow on the Hill

Contacts

+44 73116 53496

roopa.s@physiogenics.co.uk

Address

Dandi On The Hill, 59-65 Lowlands Rd, Harrow HA1 3AN

Opening Hours

Monday-Sunday 9 AM to 7 PM (last appointment at 6PM)

We are here when you need us. 7 Days a week